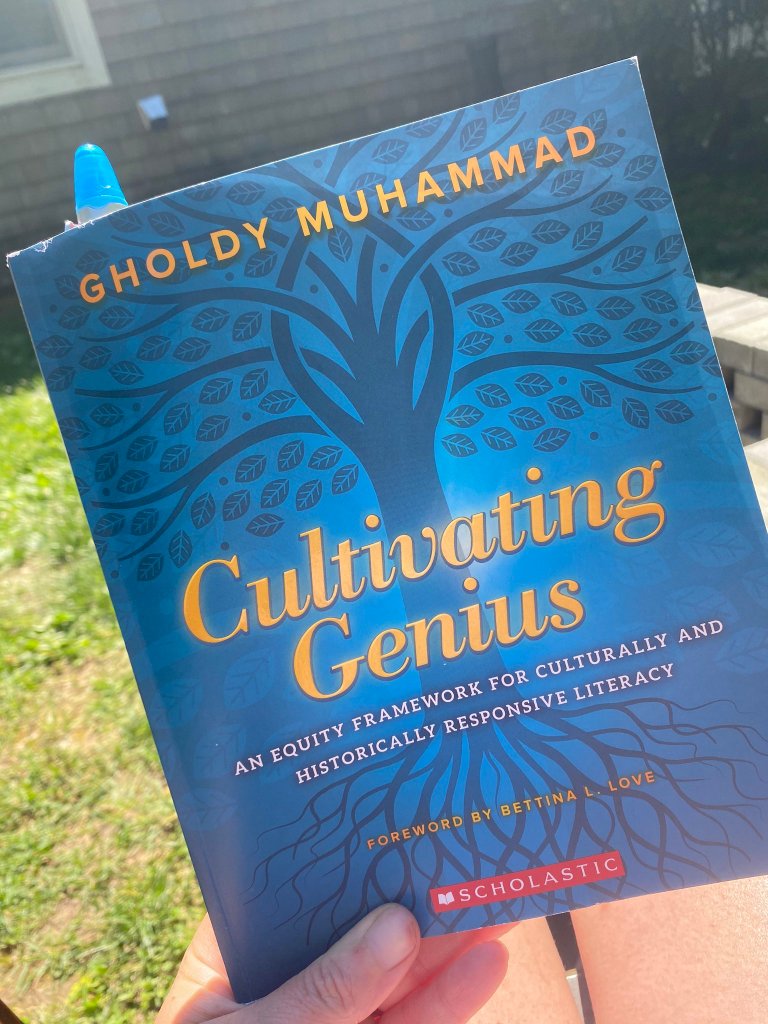

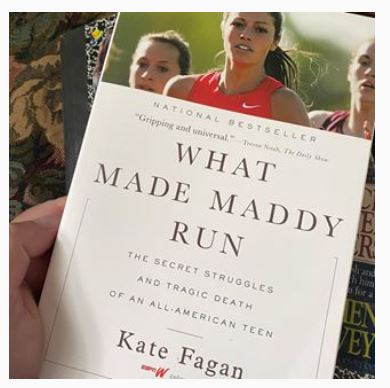

One of the best things I did for myself this year was sign up for the Book Love Summer Book Club to benefit the Book Love Foundation. I enjoyed each of the texts selected for us this year, but the one I just finished – Kate Fagan’s What Made Maddy Run: The Secret Stuggles and Tragic Death of an All-American Teen – is perhaps the one that I enjoyed the most.

But how can one enjoy a book about the suicide of a young person? Well, no… it is not the subject matter that was enjoyable. Not at all. The subject itself is heartbreaking.

It’s Fagan’s manner in telling Maddy’s story that was most profound to me.

In the book’s Foreword, ESPN The Magazine Editor in Chief Alison Overholt wrote, “Great narrative journalism has long been about helping us to understand universal truths of the world by grounding big ideas in the stories of real people.”

The depression that had a stranglehold on college Freshman Maddy Holleran, the stranglehold that eventually led her tragic death, is a subject of universal truth that clearly needs to be addressed quite a bit more.

I reveal no spoilers when I tell you that Maddy Holleran ended her life in 2014 by taking a running leap from the top of a parking structure in downtown Philadelphia.

This event is not the focal point of the story. Instead, Fagan endeavored to examine what could have caused Maddy to make this choice. This final, irreversible choice.

I am not a mental health professional, but I know enough about suicide to understand that it doesn’t exist in a vacuum. The problem is that nobody wants to talk about suicide, and nobody wants to talk about suicide in the presence of kids. It’s almost as if mentioning the word or bringing up the topic in class dissolves some invisible protective barrier surrounding young adults that keeps them safe from suicidal ideations.

So in not discussing suicide, we often too ignore what leads to it: unrelenting personal pressure, anxiety, depression. While all of us battle these demons to one extent or another, there are so many people out there, kids out there, that succumb to the demons.

I must acknowledge my own discomfort in speaking frankly about suicide with students, and I would be hesitant to make What Made Maddy Run available to students without some kind of trigger warning or disclaimer, despite the fact that I loathe the idea of both, because I cannot guarantee that a particular student wouldn’t read a book about suicide and romanticize it.

That was not Fagan’s intention, and she says to herself. I think her approach was meant to give thoughtful readers a wide berth into examination of our own thoughts on anxiety, depression, happiness, and hopelessness. We get a window into Fagan’s thoughts through occasional deviations from Maddy’s story to present first-person narrative from her own experience. These are relevant inclusions and written from a place of empathy given Fagan’s background as a college athlete who also suffered bouts of anxiety and depression.

In fact, the complete story is an interweaving of Fagan’s access to primary source documents from the Holleran family, her own personal narrative, and various third-party interviews. Fagan interviewed those who knew and loved Maddy as well as others who, from their own experience, could offer either anecdotal or expert insight to illuminate Maddy’s mindset. This approach gives the reader a panoramic view of the tragedy through multiple perspectives. We are able to read Maddy’s text conversations with friends, narratives for school assignments, and personal letters to her track coach. We are able to get perspectives on Maddy from her parents, her friends, her friends’ parents, and her coaches. We get Fagan’s perspective, and we get perspectives from Fagan’s carefully-selected interviewees.

The phrase posted in the title of this entry comes later in the book, in a chapter titled, “The Rules of Suicide.” Here Fagan interviews Dese’Rae Stage, suicide survivor-turned-activist whose work aims to humanize survivors and bring light to the need for thoughtful and frank conversation on the topic of suicide. It was she that said, “…denying its existence isn’t helping anybody,” pointing out that we need to be able to talk about suicide in a safe way.

Stage adds, “I would like to imagine that the silence, or the inability to talk about it in healthy ways, directly relates to more suicides. “

One of the more interesting discussions in our Book Club chats centers with bringing Maddy’s story to the classroom. Can we do it? Should we do it? That’s tricky.

I recall a school psychologist I worked with, since retired, who had no problem projecting her frustration upon me when topics such as date rape, assault and suicide came up in English class. She said that such discussions drove fragile students into a state of panic, overflowing her office with urgency.

“You need to stop teaching Speak,” She would often say, adding that I had no idea how traumatizing the story was to kids who were themselves victims of sexual assault.

I see the point. I see it clearly. As a caring educator, the last thing in the world I would ever want to do is bring pain to a student.

But a teaching colleague also made a good point; “Isn’t that what discussion of these texts is supposed to do? Help us find the kids who need help so we can get them that help?”

So what do we do in the best interest of kids? I don’t have an answer, but I know this: Reading and discussing Speak in class is not going to bring an end to sexual assault, but neither is not reading and discussing Speak. Some students, whose own life experience is painful, will be reminded of that fact. Other students may develop an awareness of how sexual assault does long-term harm to a victim. Hopefully this awareness leads to empathy. Hopefully that empathy leads to a lifetime of “doing the right thing.”

How to introduce this text to students is a question I would like to explore with my colleagues: school psychologists, social workers, administrators, teachers, and coaches.

In the meantime, I do think the following people should read What Made Maddy Run:

- Secondary educators, especially those who are coaches. In another post, I plan to delve more deeply into the book as read from my own background as a student athlete, a coach, and now an official. Doing that here would have made this post long and unbearable.

- Parents of teenagers or pre-teens, especially those who are parents of student athletes. I will argue that Maddy’s parents did everything they could to support their daughter and get her the help she needed. Though I’m sure they live with the regret and guilt that naturally comes with losing a child to suicide, they didn’t do anything wrong. The pressure Maddy faced was self-imposed. They recognized that, and they did the best they could to help her.

- Those who lost someone they love to suicide. I lost a good friend from college, who took her own life at the age of 28. This came as a shock to all who loved her, as she always exuded (what seemed to be) pure happiness and contentment with the world. I, too, felt a whole ton of guilt after it happened, trying to go backwards and search for any signs I might have missed that she was in trouble, any cries for help. Reading Maddy’s story helped me to understand that sometimes there are no signs, and we need to make peace with that. Before Kate Fagan came along to write this book, Madison Holleran was the author of her own life story. She published it on social media for the world to read. She sent it with her text messages. Everything that was plaguing her so deeply was internal, with only those closest to her knowing that she had some challenges, and with nobody knowing how extensive those challenges really were.

Can a book make you uncomfortable and still be enjoyable at the same time? Yes. It was wholly because of Kate Fagan’s thoughtful, respectful and skillful execution.