From Focus on excellence, not perfection by Naphtali Hoff. The full text of this article is here.

Before I dive in here, let me explain what writing “from” something means.

What you see here was inspired, in some way, by the article I linked above.

This is a concept I’ve come to understand from reading and learning from educators such as Kelly Gallagher, Penny Kittle, and Linda Rief. One thing I’d like to do this year (that is, as I chase my non-resolution to create more) is to use texts as sources of inspiration for my own writing.

I’m mentoring an aspiring administrator this year, which is a first for me. As I brainstorm a list of things I’d like for her to take into her first administrative role, my mind goes to some conversations I’ve had with colleagues about lesson observations. That is not what Hoff’s article is about; however, reading that first and coming back to this might offer some additional context for the brain dump that follows. It’s a response, but it’s not a response. Perhaps its better to explain it as an idea that leapt from the platform of the one that came before.

I’ve been a school administrator for nearly seven years. In the context of my role, I conduct one formal observation for each veteran (tenured) teacher that I supervise, and at least two formal observations for probationary teachers. Most of the teachers I work with are around my age, give or take a few years. We have at least 10 – 15 years of classroom experience, with much of that from the same school district. Sometimes that experience is tipped, if not exclusive, to one or two grade levels.

Mr. Jones* has been teaching 9th grade English for about twelve years. He’s an excellent teacher, often one of students’ favorites in their high school days. His lessons are thoughtful and creative, at least as far as I can tell… In the seven years that I’ve worked with Mr. Jones so far, he has consistently arranged for me to observe him teaching one of his tried-and-true, already exemplary lessons. Each year it seems that I see a lesson that Mr. Jones has had plenty of time to develop, self-assess and perfect. Our pre-observation meetings are typical: Mr. Jones shares a summary of the lesson I will see, and he explains the context of where it falls in the unit. Sometimes this idea is accompanied with an already-written lesson plan, sometimes it is not. Either way, Mr. Jones speaks through his plan expertly, confidently, justifying each procedure and explaining with explicit detail how long each activity will take. His matter-of-fact demeanor suggests that he is neither looking for nor wants questions or suggestions. If I’m being honest, I don’t often have any questions or suggestions because everything is plausible and clear. Mr. Jones already knows that this lesson has been field tested and perfected. While he can’t always control for what will happen in class that day, more often than not, everything goes as just as expected…just as he planned.

Ms. Davis* is also a veteran teacher. Though I suspect she’s been in the classroom for the better part of twenty years, she’s bounced between different grade levels and between the middle school and high school. For the last eight years, Ms. Davis has been teaching 8th grade exclusively. Ms. Davis rarely comes to our pre-observation meetings with a solid lesson plan. More often than not, she has an idea, a seed. Our conversations fascinate me because she walks me through her metacognitive processes, and I watch that idea become a plan. While Ms. Davis doesn’t usually ask for feedback or suggestions, she’s open to both. She welcomes my questions, and she does not feel challenged by them. It might be fair to say that Ms. Davis has no clue what’s going to happen when I see her class for our observation. She will often say, “This sounds good in theory, but I’m not sure how it will go in practice.” Sometimes her lessons are executed beautifully. Sometimes they tank.

I am the direct supervisor for both teachers, and I’m the only administrator who has seen them every year for the last seven years. In that time, Mr. Jones has not demonstrated, at least to me, any growth in the design or execution of his lessons. Nada. Zip. Zilch. Now I am smart enough to know that Mr. Jones, because he is such a great teacher, is often experimenting with new lessons and ideas. For whatever reason, he chooses not to show them to me. Ms. Davis, while not particularly proud of those lessons that fail while I’m in the room, is at least OK with it.

I actually love the bad Ms. Davis lessons, and others like them. They make me feel useful, at least, as there is an opportunity for the two of us to roll up our sleeves. We can consider what went wrong from both perspectives, and we can work together to fix it. I learn so much about good teaching from these exchanges.

I don’t so much love the Mr. Jones lessons. While I got to see a nice show, I’m not being utilized well for the observation. I can give nothing but praise and validation. There’s nothing to fix, nor is there anything to suggest. Gold star.

I’ve spent a lot of time reflecting on why far more folks share the same mindset as Mr. Jones, “My supervisor needs to see a perfect lesson.” I don’t have an answer, but I have this… In my own classroom days, I’ve had excellent supervisors, and I’ve had terrible supervisors. I’ve had supervisors who were compassionate and real, and from whom I’ve learned a great deal. I’ve had others who did things like use the chromebook I offered to follow along with an activity to check e-mail and do some shoe shopping, or forget to swap English for math in the paragraphs they clearly copied and pasted from another teachers’ observation to mine.

This is not hyperbole. These things actually happened to me.

But perhaps those not-so-good experiences that I’ve had with certain supervisors taught me, more than anything else, that this role needs to be taken seriously. We will never earn respect if we don’t give the task the respect it deserves. We will never earn trust if we dole out “developing” scores punitively.

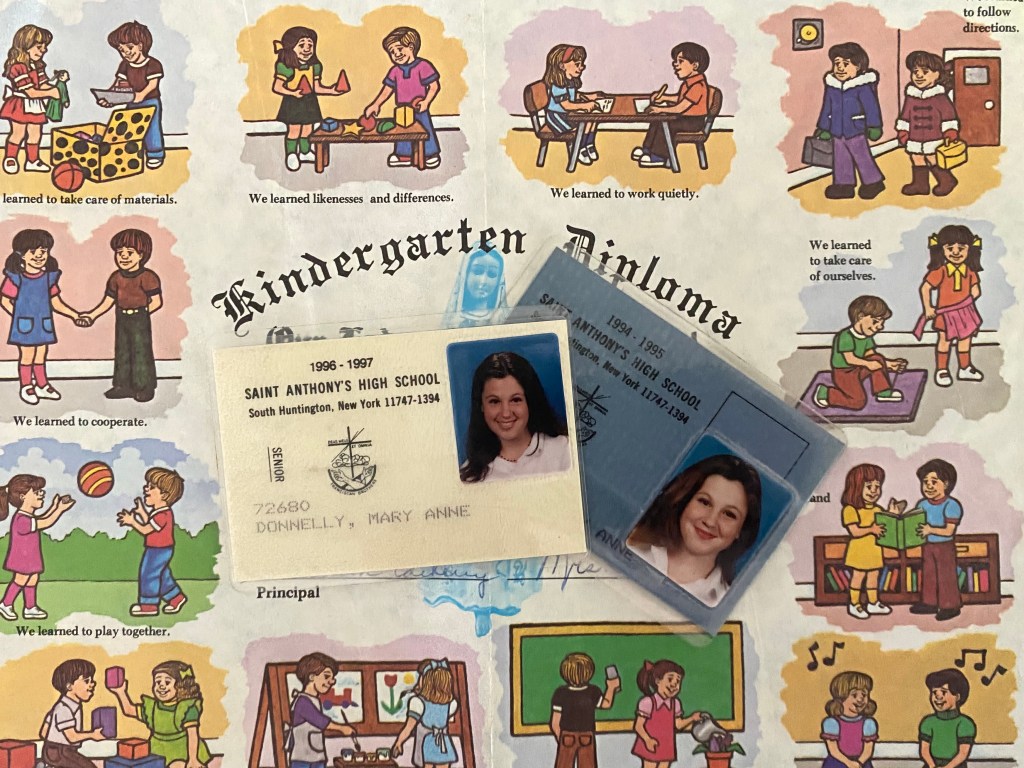

I’ve also learned from my good experiences. Our relationships with our colleagues need not over-emphasize hierarchy. School administrators like myself are neither experts or gurus. We can’t let our egos lead us, no matter how many gold stars we ourselves received on our Danielsen rubrics. While I’ve learned so much about good teaching from the context of this role, and while I’m confident that I could be a better teacher tomorrow than I was on my “best” days from 2000 – 2015, I know there is no way I’d be able to pull off executing mistake-free lesson plans for the rest of my days. Absolutely not.

But I can promise this… I will not fear those mistakes in front of a supervisor who works hard to earn my trust, who takes the process seriously, and is going to do what she can, however much or however little, to help me be the best teacher I can be.

I wish all of my teaching colleagues were more like Ms. Davis and less like Mr. Jones. I wish all of my teaching colleagues knew that its ok to be vulnerable. It’s OK to take risks. It’s OK to step away from their comfort zones when I’m in the room.

I celebrate those moments in pre-observation meetings when teachers indicates that they are trying something new and are not sure how it will go. If I’ve earned their trust, if I’ve walked my talk, they will never see any feedback from me as “judgey,” and the narrative I will eventually write to accompany a not-so-great lesson will certainly never, ever be punitive. I know that there are performance indicators on that rubric that run the gamut from awesome to awful, but I make no apologies in saying that, in my opinion, an effective or a highly-effective teacher is not made so by the language of a rubric. In my eyes, the truly highly-effective teachers are the ones that leave room for growth, no matter how long they have been teaching.

This is a plea to all of my fellow administrative colleagues: please do not create an environment where the teachers you supervise feel like they’ve done something wrong if their lessons aren’t perfect all the time. Let teachers know that it is safe to take risks in lessons that will be observed. How else can they get authentic feedback from a colleague? Please behave in a manner that celebrates the occasional failure as a teachable moment. If something goes wrong, or if something can be improved, don’t check the “bad box” write about it in the narrative… roll up your sleeves and offer to help. Allow a do-over. Show your colleagues that it is OK to be vulnerable by acknowledging that we all make mistakes. None of us are perfect. The best we can hope for, in all circumstances, is growth.

If you want to do any of the things I mentioned above, but you are fearful that your supervisor simply won’t have that, feel free to print this blog post and share it with them. As a matter of fact, give them my phone number, too. I might be small, but I’m mighty.

That being said, even after seven years, I have so much more growth to accomplish. I need to find a way to make Mr. Jones and teachers like him feel more comfortable showing me a lesson that needs peer feedback. I need to find a way to create a circumstance where he can accept that feedback without losing confidence. I’m working on it.

The good news is that I have a number of exemplary role models and leadership mentors less than a phone call or a five minute drive away. I am blessed to have learned what I have from their leadership. If I, if we, ever figure this out, I’ll let you know!

*Mr. Jones and Ms. Davis are fictionalized characters, created as amalgamations of real people and real situations I’ve encountered both as a teacher and as an administrator.